The Supreme Court has concluded that the regulation governing the deduction for new fixed assets in the Canary Islands is Article 26 of the 1978 Corporate Income Tax Law and not, contrary to what the tax administration and majority jurisprudence have been defending, the 12th Additional Provision of the 1995 Tax Law.

The Law 61/1978, of December 27, on Corporate Income Tax (“1978 Law”) regulated a deduction for new fixed assets (DNFA) for common territory, which was repealed by the subsequent Law 43/1995, of December 27 (“1995 Law”) for fiscal years starting after 1996. For fiscal years beginning in 1996 itself, however, this latter law allowed the continued application of the deduction, which was regulated in its 12th Additional Provision (AP 12).

In order to maintain the application of this deduction in Canary Islands territory in case it was eliminated in the rest of the common territory, the Fourth Transitional Provision (TP 4) of Law 19/1994, of July 6, modifying the Economic and Fiscal Regime of the Canary Islands, established that “in the event of suppression of the General Regime of Deduction for Investments regulated by Law 61/1978, of December 27, on Corporate Income Tax, its future application in the Canary Islands, until an equivalent substitute system is established, will continue to be carried out in accordance with the regulations in force at the time of suppression”.

Since then, there has been a debate about which regulations should govern the DNFA in the Canary Islands from January 1, 1997 (the fiscal year from which, as anticipated, the deduction ceased to apply in common territory, although it could continue to be applied in the Canary Islands). According to the predominant thesis (defended by the tax administration and reflected in numerous binding resolutions of the General Directorate of Taxes, as well as in the orders approving self-assessment models), the DNFA was governed by the AP 12 of the 1995 Law, as this regulation was, with respect to the deduction, an equivalent substitute system in the terms established by TP 4 of Law 19/1994. The minority thesis, but supported by some rulings of economic-administrative and contentious-administrative courts (mainly the High Court of Justice of the Canary Islands), was inclined to understand that AP 12 of the 1995 Law was not an equivalent substitute system, but a transitional regime applicable (in common territory) only in the 1996 fiscal year, so the regulations that should govern the DNFA in the Canary Islands were those in force at the time of its general suppression, that is, Article 26 of the 1978 Law.

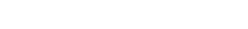

In its judgment 605/2024, of April 10, the Supreme Court ends this debate, establishing as doctrine that the regulations applicable to the DNFA is the system contemplated in Article 26 of the 1978 Law (and its regulations, approved by Royal Decree 2631/1982, of October 15). The resolution of this debate has important implications for the practical application of the incentive, given that its regulation in the two disputed norms differs in key elements of the deduction’s configuration. Without aiming to be exhaustive, the following can be noted as fundamental differences:

From a practical point of view, we are faced with the existence of two successive and opposing criteria, which raises doubts regarding the principle of protection of legitimate expectations. However, following the most recent criterion of the TEAC, it seems reasonable to conclude that (i) self-assessments submitted in fiscal years prior to the Supreme Court ruling in accordance with the 12th Additional Provision should be protected by this principle, while (ii) those submitted after the publication of the ruling should be made in accordance with the provisions of Article 26 of the 1978 law.

In any case, there are numerous controversial situations that may arise in the future due to the interplay of one regulation and another (especially, for example, for taxpayers who decided to make investments in 2023, before the publication of the ruling, but having to submit the self-assessment after said publication), as well as the obligation to apply a 1978 law and a development regulation that, in some of its articles, seem contradictory. Added to this is the fact that these regulations are not adapted to current accounting principles, nor to the EU State aid framework in which the tax incentives of the Canary Islands Economic and Fiscal Regime are framed. Therefore, it would be desirable that, for the sake of legal certainty, the legislator intervene by definitively configuring a secure and stable tax legal framework for taxpayers in this area.